Ancient intellects are now being guarded by artificial intelligence following moves to protect one of the most extraordinary collections of historical manuscripts and documents in the world from cyber-attacks.

The Vatican Apostolic Library, which holds 80,000 documents of immense importance and immeasurable value, including the oldest surviving copy of the Bible and drawings and writings from Michelangelo and Galileo, has partnered with a cyber-security firm to defend its ambitious digitisation project against criminals.

The library has faced an average of 100 threats a month since it started digitising its collection of historical treasures in 2012, according to Manlio Miceli, its chief information officer.

“We cannot ignore that our digital infrastructure is of interest to hackers. A successful attack could see the collection stolen, manipulated or deleted altogether,” Miceli told the Observer.

Cyber attacks were increasing, not slowing down, he added. “Hackers will always try to get into organisations to steal information, to make money or to wreak havoc.”

The library, founded in 1451 by Pope Nicholas V, is one of the world’s most important research institutions, containing one of the finest collections of manuscripts, books, images, coins and medals in the world. The digitisation of 41 million pages is intended to “preserve the content of historical treasures without causing damage to the fragile originals”, said Miceli.

But he added: “This project is about a lot more than just physical preservation. Swaths of history, previously explored only by white-gloved historians, are now made available to anyone with a internet connection. This is a huge step for educational equality.”

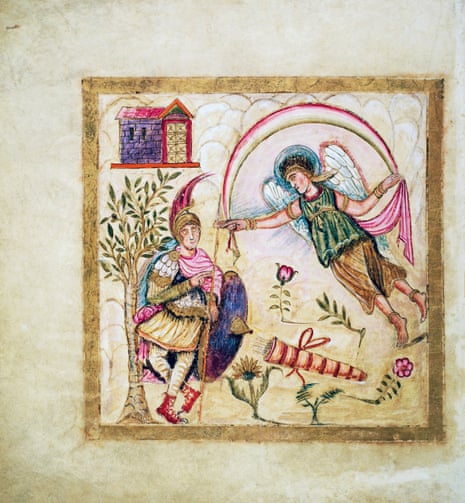

So far, about 25% of the library’s documents have been digitised. The project started with “unique, most famous and fragile pieces”, said Miceli. They include one of the world’s oldest manuscripts, an illustrated fragment of Virgil’s Aeneid that dates back 1,600 years. The collection also contains Sandro Botticelli’s 1450 illustration of the Divine Comedy; poems, technical notes and sketches by Michelangelo; ancient manuscripts of the Inca people; and historical treaties and letters.

But, said Miceli, digitisation means “we have to protect our online collection so that readers can trust the records are accurate, unaltered history”. He added: “While physical damage is often clear and immediate, an attack of this kind wouldn’t have the same physical visibility, and so has the potential to cause enduring and potentially irreparable harm, not only to the archive but to the world’s historical memory. In the era of fake news, these collections play an important role in the fight against misinformation and so defending them against ‘trust attacks’ is critical.

“Less Hollywood, but still concerning, is a ransomware attack on the library – a well-known attack that infiltrates companies unseen and then locks down files incredibly quickly until you pay a hefty sum. Ransomware today moves at machine-speed, outstripping humans’ ability to spot and stop the attack before it escalates.

“These attacks have the potential to impact the Vatican library’s reputation – one it has maintained for hundreds of years – and have significant financial ramifications that could impact our ability to digitise the remaining manuscripts.”

The library has partnered with Darktrace, a company founded by Cambridge University mathematicians, which claims to be the first to develop an AI system for cybersecurity. Miceli said: “You cannot throw people at this problem – you need to augment human beings with technology that understands the shades of grey within very complex systems and fights back at machine speed.”

AI “never sleeps, doesn’t take breaks and can spot and investigate more threats than any human team could. It makes decisions in seconds about what is strange but benign and strange but threatening.” But, he added, there was no 100% guarantee against attack. “The only way to make an organisation completely secure is to cut it off from the internet. Our mission is to bring the Vatican Library into the 21st century – so we won’t be doing that any time soon.”

Dave Palmer, director of technology at Darktrace, said cyber-attackers were constantly looking for ways “to make a quick buck or to cause embarrassment on the global stage”.

He added: “Many organisations like the Vatican library have accepted this reality. With AI, they are discovering the subtle, unusual activity that precedes a full-blown attack, and, crucially, trusting AI to fight back on humans’ behalf before it’s too late.”