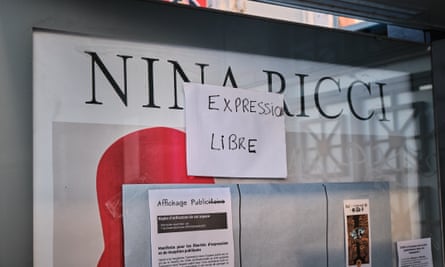

On a pavement in the northern French city of Lille, an advertising panel rotated pictures of bargain Aldi prawns and blended scotch whisky, competing for the average three-second attention span of pedestrians. Suddenly a 31-year-old hospital nurse darted across the street, unrolled a mass of white paper and began to cover the ads.

“I’ve been treating sick people in emergency rooms for 11 years, but this is about treating a sick society,” he said, as he reached up with other protesters to tape the paper in place. “When you walk down the street, how can you feel happy if you’re constantly being reminded of what you don’t have? Advertising breaks your spirit, confuses you about what you really need and distracts you from real problems, like the climate emergency.”

Passersby began to gather, some baffled, some nodding. Police officers arrived to move the demonstrators on, but they were already on the move, hurrying down into the metro to cover their key target: digital video screens advertising trainers.

For decades France has had one of the most well-organised anti-advertising movements in the world, ranging from guerrilla protests with spray-cans to high-profile court cases. But now the boom in what is artfully called “digital-out-of-home advertising” – eye-catching video screens dotted across urban areas, from train platforms to shopping centres – has sparked a new spate of French protests, civil disobedience and petitions.

High tech video billboards are multiplying in city spaces across the world, woven into the fabric of everyday life, from ribbon videos down escalators on the London underground, to French metro corridors, New York taxis, bus-shelters, newspaper kiosks, and – increasingly – broadcast from shop windows onto the street. They are becoming more sophisticated and interactive, with the potential to collect data from passersby; increasingly bright and inescapable – impossible to click off or block like you can online. But in France, there is fresh debate on how urban planners and local councils should limit them in the public space for the sake of our overloaded eyes and brains.

The trend to squeeze every bit of city downtime into an opportunity to place people in front of screen has become a political battle on the left. François Ruffin of the French left party, La France Insoumise, recently tabled a French parliamentary amendment to ban video ads above urinals and toilets. It was dubbed the “Pee in Peace” motion. Ruffin said he was horrified when standing at a Paris café urinal to be visually “assaulted” by a video advertising Uber, a bank, and the book and tech store Fnac. “Who doesn’t enjoy that rare moment of calm: having a piss?” he wrote in the amendment, warning that since 2015, over 2,000 of the screens had “colonised” 1,200 urinals in 25 French towns.

Lille, a former centre of northern French industry and now a hub for artists, designers and students, has become the focus of the latest battle over screens in the public space. Like many French cities, the Socialist city hall has sought limits on advertising video screens, meaning no street furniture on pavements carries commercial video ads. But in France those rules don’t cover train stations or public transport, where video advertising is flourishing – particularly 10-second clips for Netflix, Amazon and film releases. When the local transport body for the greater Lille area recently fixed a new contract that could boost the number of video screens to around 160 – including in bus shelters – the city hall was furious, but largely powerless because the deal was legitimate.

“This type of screen in the public space would be invasive and intrusive, consume too much energy, distract motorists and get children even more hooked on videos than they are already,” said Jacques Richir, a Socialist deputy mayor. “It would mean advertising messages [infest] the urban landscape, when we want to limit them.”

Local representatives of the greater Lille area, the Métropole Européene de Lille, met this month to debate new local advertising rules, which protesters hope will take a tougher line on screens. Lyon, France’s third biggest city, also moved this month to fund a new electric bike-scheme itself rather than strike a deal with outdoor advertisers which might have led to introducing video-screen ads in the city.

But there are other loopholes on French pavements. In Lille, as in Paris, shops are considered private spaces, and not subject to local advertising rules. So all kinds of shopfronts – from chemists to hairdressers and tech shops to trainer emporiums – can put up screens just behind their windows, beaming digital video into the street.

“It’s crazy,” said Fabien Delecroix an IT teacher from the Lille branch of anti-ad campaigners Résistance à l’Agression Publicitaire. “If someone stood naked at their window right on the street deliberately showing their body, you wouldn’t say: ‘Oh that’s fine, they’re technically not exposing themselves because they’re in their own home.’”

Meanwhile, the courts in Lille are cracking down on protesters. At a hearing last month, flanked by supporters, Alessandro di Giussepe, a 42-year-old actor, who once stood for local election dressed as a joke “pope” of consumerism, was fined €900 (£758) for defacing adverts in the city with black pen as an act of civil disobedience. A father in a passing car had called the police, compl defacing ads was setting a bad example to children. Di Giussepe said adverts destroyed “public space, which is our shared space”.

“It won’t stop us,” said Marion, from the Lille anti-advertising protest collective Les Déboulonneurs. “We’re told children shouldn’t be exposed to screens before age three, but in pushchairs they’re craning their necks at the screens all around them in public.”

The French firm Mediatransports, which runs 1,250 video screens in French rail stations, as well as 700 on the Paris metro – including 150 in Paris’s Gare du Nord alone – said digital screens were excellent at reaching commuters. “They generate more revenue than paper ads, because they can quickly adapt to advertisers’ needs – changing a message for the exact time of day or even the weather.”

With French local elections in March, Grenoble’s Green mayor, Eric Piolle, is running for re-election four years after styling his city at the foot of the French Alps as the first European urban centre to ban commercial street advertising. Piolle replaced more than 300 paper advertising signs with trees or community noticeboards, although bus and tram stops still carry adverts, which the city said it had limited. He said it was no surprise that ad screens and their mental and environmental impact was the next frontier in what politicians should ban. “Public space is a meeting space so lowering the aggression of advertising is positive for everyone,” he said.

Paris is also soul-searching about advertising. Early last year, the capital’s more than 1,600 advertising signs – large grey paper advertising panels on pavements – disappeared for around 18 months during a protracted process to find a new contract. No one noticed their absence, but when they were gradually put back this autumn — the same number in virtually the same spots — many residents complained of an advertising onslaught.

“I’ve never seen so many people annoyed about advertising. People are coming up to me saying this sign is taking up half the pavement,” said the long-time anti-advertising campaigner Thomas Bourgenot, of Résistance à l’Agression Publicitaire in Paris. A petition by Greenpeace Paris and other groups has called on the city to ensure there can be no future arrival of commercial video ad screens, which are currently banned on street furniture.

The city hall said its policy was not to develop any more advertising in the city, and to fight the illegal ads so often plastered or beamed across buildings. A spokeswoman said the size of ads had been reduced and a portion of street furniture given over to city messaging.

The row in French cities is likely to continue. Historically, advertising took off later in France than in the UK and US, with French newspapers in the 1930s calling it a “school of lies”. Today, however, France is home to some of the most influential advertising firms and lobbies in the world.

“For a very long time, French intellectuals associated advertising with something destructive to culture, going back to Voltaire and beyond,” said Caroline Marti, professor of the science of information and communication at the Sorbonne. “There was a criticism that advertising was anti-democratic, and a very strong idea in France that public space belongs to everyone, that we pay for it with our taxes, which are relatively high, and that the public space is where we go to demonstrate.”

In Lille, Martine Cosson, 74, a retired paediatrician among the anti-ad protesters, said: “Digital video screens in public spaces have an effect on our brains, whether we want them to or not, so planners and politicians should answer to that.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter